Reclusive Artist: Joseph Cornell & Fernando Pessoa

Untitled (The Hotel Eden) (c. 1945), Construction, 15 1/8 x 15 3/4 x 4 3/4 in

It may be argued that some of the most mysterious, paradoxical art has been produced by reclusive souls. There are many and I do not intend to list them all. But some of these artists and literary figures whose work I return to again and again share this same quality. Henry Darger, Fernando Pessoa, and Emily Dickinson are among my favorites. Equally, we could say that Kafka, Whitman, and Thoreau (while writing Walden) cultivated their art amid the deepest solitudes.

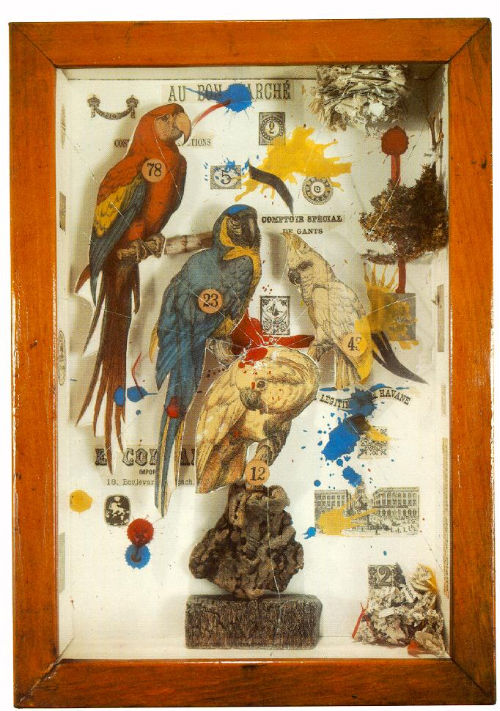

Habitat Group for a Shooting Gallery (1943), Construction, 15 1/2 x 11 1/8 x 4 1/4 in

Joseph Cornell is another artist who lived a fairly reclusive life. His father died of a blood disease in Joseph’s early teens, and his younger brother developed a severe form of cerebral palsy at age one. Joseph devoted himself to taking care of Robert, his younger brother, until Robert died at age 54. The two siblings lived with their mother in a single-family home in Queens, New York.

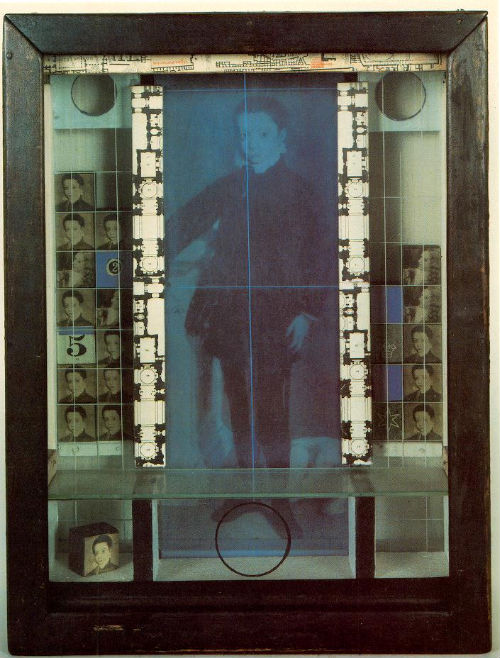

Untitled (Penny Arcade Portrait of Lauren Bacall) (1945-46) Construction, 20 1/2 x 16 x 3 1/2 in

But there are different types of artist recluses, and Cornell most reminds me of the Portuguese writer, Fernando Pessoa. Both recluses identified strongly with their urban environments; the city was part of their solitude. For Pessoa, it was Lisbon; for Cornell, Queens and Manhattan. In an insightful article on Cornell, Adam Gopnik from The New Yorker writes:

Though Cornell was isolated neither in his work (more people came out to Flushing than visited Max Beerbohm in Rapallo) nor in his art (he had galleries and collectors from early on), he was isolated in another sense, by choice. He had discovered the joys of solitary wandering. Beginning in the early nineteen-forties, his life was structured by a simple rhythm: from Queens via the subway to Manhattan, where he walked and ate and watched and collected, and then back home to the basement and back yard in Queens, where he built his boxes, talked to his mother, and cared for his brother. The flaneur and the recluse were equally intense. Cornell chose to be that classic New York thing: a walker in the city.

Untitled (Medici Boy) (1942-52), Construction, 13 15/16 x 11 3/16 x 3 7/8 in

But what is it about Joseph Cornell’s boxes that provokes such deep curiosity? I’ve been to the Modern Wing of the Art Institute of Chicago to view Cornell’s boxes six or seven times. It is not enough to say that these works are enchanting, though they are certainly that as well. First we have to consider that these are not paintings, nor sculptures, they are not drawings or conceptual works. The three dimensional box under glass is a singular medium. Our unfamiliarity of it as a work of art may be the first thing that strikes a viewer.

Untitled (Medici Princess) (c. 1948), Construction, 17 5/8 x 11 1/8 x 4 3/8 in

Beyond that, the three dimensional box under glass is something we peer into rather than simply observe. The box contains things, collage elements, found objects, various depths and surfaces, multiple textures. The medium shares the quality of an artist’s book in the sense that the viewer enters it; concealment is as much a part of the work as its visible aspects.

Untitled (Medici Prince) (c. 1952), Construction, 15 1/2 x 11 1/2 x 5 in

Again I’m going to refer to Fernando Pessoa to make a comparison to Cornell’s art. The mystery and paradoxical nature of both of their works (and with Pessoa, I’m referring to The Book of Disquiet) stems from a major characteristic of the reclusive artist: deep and profound longing. For Pessoa, it is an existential longing; a longing to be someone else, someplace else. The narrator’s intense dream-life overlays his quotidian existence. But Pessoa’s (or the main character, Bernando Soares’) longing is not the sentimental kind; it is burdened with a self-conscious awareness of his own illusions. This passage epitomizes the complexity of Pessoa’s impossible longing:

I myself, who just said I would like a cabin or a cave where I would be free of the monotony of everything, which is my own monotony, would I dare to leave for that cabin or cave, knowing beforehand that since the monotony is mine, I would always have it with me? I myself, who suffocate where I am and because I am, where would I breathe better, given the fact that the illness is in my lungs and not in the things that surround me? (p. 52 trans. Alfred Mac Adam)

Untitled (Paul and Virginia) (c. 1946-48), Construction, 12 1/2 x 9 15/16 x 4 3/8 in

Pessoa’s impossible longing, which is existential and literary, is not the same as Cornell’s, which is emotional and nostalgic. Cornell’s longings grew out of his infatuation with the beautiful young girls he found on his solitary wanderings through New York. Gopnik writes:

But he could fall in love with almost any woman. His infatuations with the great ballerinas of the emerging City Ballet are famous; Allegra Kent, who really was a fée, and nearly as original as he was, became a friend. But he had the same feelings about some pretty improbable movie stars. Lauren Bacall and Marilyn Monroe, O.K., but he was also crazy about Sheree North, a now forgotten smoky-voiced soubrette of the fifties.

Untitled (Soap Bubble Set) 1936, Construction, 15 3/4 x 14 1/4 x 5 7/16 in

How did Cornell’s longings take shape in his glass-covered boxes? Many of them were gifts to his favorite actresses; perhaps shrines to his personal goddesses, or fairies (as he called them). Parallel to these motivations is the very nature of the boxes themselves. They contain old things, they preserve found objects, they hold photographs, maps and constellations. The glass-covered boxes seem to retain the present; which has now become the past.

Verso of Cassiopeia 1

In The Book of Disquiet, during the brief interims of Bernando Soares’ workaday life as an assistant bookkeeper, he dreams, he fantasizes, he imagines himself elsewhere. He would like to be a celebrated writer, but knows this is pure fantasy. He feeds these fantasies with internal monologues, and records these “dreams” in his diary. But he’s keenly aware of the brutal, mundane reality of the life he lives. Similarly, Cornell created boxes filled with longings, spirits even, that could never escape; could never become reality. It’s this living contradiction of the reclusive artist that unites them both.

Untitled (Apollinaris) (c. 1954), Construction, 15 15/16 x 9 3/4 x 4 3/8 in.

Gopnik sums it up brilliantly here:

What’s nostalgic is that, behind glass, fixed in place, the new things become old even as we look at them: it is the fate of everything, each box proposes, to become part of a vivid and longed-for past, as real and yet as remote from us as the Paris hotel we never got to.

Untitled, (c. 1957-1958), mixed media 17 3/8 x 12 7/8 x 3 1/2 in.

Reclusive artists build interior worlds so vast that their language is the paradoxical and mysterious language of life itself. Both Joseph Cornell and Fernando Pessoa created art that dramatized our own impossible longings.

Special thanks to Web Museum and Smithsonian American Art Museum for image credits!

Also check out this multimedia exhibit of Cornell’s works at PEM

I’m the founding editor of Escape into Life, online arts journal.

I’m the founding editor of Escape into Life, online arts journal.

Great article — I may need to rent some movies starring the actresses Cornell was inspired by.

[…] original here: The Reclusive Artist: Joseph Cornell and Fernando Pessoa | Escape … By admin | category: CORNELL | tags: batman, been-produced, CORNELL, dynamic, knight, […]

This is a rather good welcome mat at the door of Cornell's world. A few clarifications and observations:

Although you qualify it somewhat, I think it is wrong to refer to Cornell as a reclusive artist. As Gopnik points out, Cornell regularly received visitors at the house on Utopia Ave. (he always offered them little coffee cakes); he was regularly exhibited and attended openings; and he carried on extensive correspondences. A better term, I think, would be “solitary artist.” “Reclusive” suggests an active avoidance of human contact, and this certainly wasn't the case for Cornell. Rather, a combination of family obligation and his own quiet, contemplative nature kept him on the periphery of the New York art world that others hungrily dove into.

There are a number of keys to understanding Cornell's work. In fact, “understanding” is probably not the best word, as Cornell never intended his boxes to mean anything. They are meant to be inhabited and experienced, not understood. One key that you mention here is the sense of longing and nostalgia. There is also a sense of narrative in his work. You have a feeling that a story is being told but that it is only being presented to you in enigmatic vignettes. It is no surprise that Cornell is frequently cited by poets and writers as a favorite artist.

The narrative being hinted at, though, is deeply personal. I consider Cornell to be the most personal (and literary) of modern American artists. Meaning cannot be extracted from Cornell's work because it is hermetic, a bell jar enclosing a swirling universe of interacting, recurrent images, sealed off from the mundane world the rest of us inhabit.

Perhaps the best way to enter Cornell's world is to see it as a modern Wunderkammer, a Cabinet of Curiosities, little wonders and gems and oddities, each displayed in a little drawer or box and suggesting the vast marvel of the Universe itself. Seen this way, Cornell's boxes are no longer understood as discrete works of art but as pieces of a grander, personal cosmos. And here we must include in this cosmos the workshop where he created, with its hand-labeled boxes full of sundry components and its file cabinets filled with dossiers of clippings from celebrity magazines and old books and maps. (The workshop is now housed in its entirety in the Smithsonian.) And we must also include the voluminous, dreamlike diaries he kept (selections from which can be found in Mary Ann Caws' “Joseph Cornell's Theater of the Mind”.) For these are as much his art as the boxes are. They are of a piece, forever talking to each other in a language that sounds familiar but which we can never translate.

This is a great response, and I realize that the term “reclusive” connotes a hermetic life . . . but in Cornell and Pessoa, we see an artist who is not sequestered from the world, and yet also (in Gopnik's words) a “self-willed” recluse.

Perhaps this implies a sort of insulated creative world, full of personal mythology. Not necessarily a misanthropic person or a hermit.

I use the term, as Gopnik uses it, loosely; well aware of the contradictions. After all, no person (or artist) is just one thing or the other.

Cornell created movies himself, the most well known of which, “Rose Hobart,” can be watched here: http://www.ubu.com/film/cornell.html

As you might expect, it's not a film in the traditional sense.

Great ART! I’m a fun of such art style!

This is a wonderful commentary. Cornell and Pessoa have both been long-time favorites of my own. Thanks for writing.

Beautifully drawn parallels between these two artists, and I am pleased to be introduced to Pessoa.

[…] […]

[…] and then almost simultaneously to the Cornell piece: the uncoiling birdsong…which I had seen first many years ago at the Art Institute of Chicago in conjunction with an exhibition of Surrealist works over which I lingered for more than a few hours each day I was there. To those fans of Cornell, let me, too, add that there is a fine little essay on the unexpected (to me) affinities between the artist and Fernando Pessoa at EIL. […]

[…] […]

[…] photo credit […]