Movie Review: Philadelphia

In 1993, Jonathan Demme lobbied TriStar Pictures to hire an actor called Ron Vawter to play a supporting role in his upcoming film Philadelphia, a movie condemning homosexual discrimination, America’s fear of AIDS and its sufferers, and the backhanded bureaucracy of large corporations who were terrified at the prospect of having openly gay employees. Vawter, playing a board member at fictional law firm Wyatt, Wheeler, Hellerman, Tetlow and Brown, gives a terrific performance with very limited screentime: his Bob Seidman is the only board member to show any remorse, and says his decision not to intervene in Andy Beckett’s case will haunt him “till the day I die”.

So why did Demme have to work so hard to get TriStar to hire him? Vawter was HIV-positive, and the company’s health insurance wouldn’t extend to cover him. TriStar wanted someone else, Demme wouldn’t settle for anyone less. It’s a devastatingly ironic side-note to a film whose very purpose is to criticise this kind of hateful discrimination. Vawter died in 1994, but this film is a poignant legacy to leave behind.

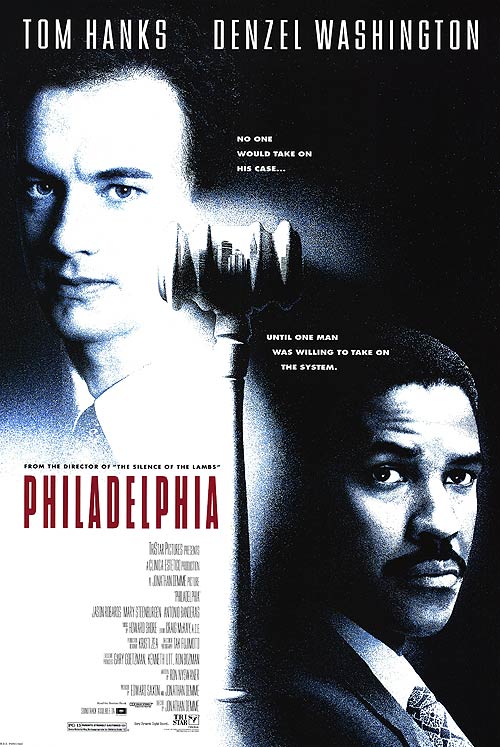

Demme’s movie follows the aforementioned Beckett (Tom Hanks), a superb young lawyer who has just been promoted and is handling a huge case at WWHTB where Charles Wheeler (a tremendous Jason Robards) is grooming him for big things; Beckett is also gay, but chooses to leave his personal life out of his work. However, when one of the board members notices a small purplish mark on his head, which he passes off as a bruise from a racketball, revelation is close at hand. Beckett collapses at home and goes to hospital, the marks gradually becoming larger and more numerous, and discovers that he has contracted AIDS. An important document inexplicably goes missing from his desk, and upon returning to the office, he is fired for ‘incompetence’: suspecting discriminatory sabotage, Andy Beckett hires small-time lawyer Joe Miller (Denzel Washington) and sues his former employers, embarking on a titanic fight for his rights…

Demme’s movie remains remarkably apposite, even 17 years after its release – although we know far more abut AIDS now than we did in 1993, there still lingers a fear of the disease and swathes of general misconceptions about its sufferers. Philadelphia, to its eternal credit, does not fall prey to these fears: although this is a film centred on a gay character, Demme never succumbs to crass stereotyping or playing homosexuality for laughs. Hanks’ Beckett is extremely bright, hard-working and talented, and is never painted as anything other than a devoted, passionate man, in his work and social lives – we are not shown explicit intimacy between Andy and his partner Miguel (an underused Antonio Banderas), rather the comfortable, comforting love a married couple might share, highlighted by the bands on both men’s left hand ring fingers.

Hanks himself offers a real gem of a performance: Andrew Beckett is a phenomenally well-crafted character and Hanks’ ability to immerse himself in such a complex role is admirable. The choice of Hanks as Beckett is just as terrific as the performance – Hanks, who so often plays the American everyman driven to extraordinary lengths (Forrest Gump, Saving Private Ryan, even The ‘Burbs), now portrays a brilliant man driven to extraordinary lengths just to be treated like everyone else. This inversion of Hanks’ familiar role makes his performance all the more impressive: whether he’s batting away homophobic remarks or losing himself in an aria in the film’s centrepiece scene, we never question Hanks as Beckett, and his barnstorming performance rightly garnered an Oscar.

Washington is also impressive, able to balance the conflicted Miller’s homophobia and desire to help his client, and this paradox is brilliantly communicated in Ron Nyswaner’s script. When Miller initially turns down Andy’s request for help, he is so afraid of the AIDS virus he has a check-up straight after the meeting, yet his admiration for Beckett’s determination enables him to overcome his prejudices, whether defending him in court or from a homophobic librarian. Although it would also be easy to align the two men based on a struggle for equality, Nyswaner and Demme never try to compare Beckett’s battle for human rights to the Civil Rights movement – to do so would undermine the film’s ‘everyone is different but should be treated the same’ message – allowing the two men’s mutual admiration to grow out of professional respect, rather than trying to make ham-fisted allegories.

An intriguing comparison one could make, however, is between Philadelphia and Demme’s masterwork The Silence of the Lambs. Demme has fallen off the map somewhat since his early ’90s zenith, and his two best films share a certain connection. Both handle a mysterious and terrifying killer, following those who are either victims (Andy Beckett) or potential targets (Clarice Starling) as they try to cope with the irrevocable changes this nightmare has brought on. Whereas death in Silence of the Lambs is often sudden and shocking, in Philadelphia it’s gradual, painful and heartrending, and whilst it would be irresponsible to claim that Hannibal Lecter is on a par with AIDS (one is fictional and one fact, for one), they are both malignant, unstoppable and deeply chilling.

Despite all the interesting subplots and allegories Philadelphia proffers, it’s difficult to claim that this is one of the truly great movies. The plot, although well-directed and supremely acted, is hackneyed on many levels – small man takes on big company, man fights for his right to die with honour, a “people are different but that’s OK!” parable – and were it not for the excellent personnel, the film could easily slip into cliché. The ending veers dangerously toward TV-movie territory (the pre-credits scene is such a blatant attempt at tearjerking it makes Beaches look like Schindler’s List) and there are a handful of wasted opportunities: Antonio Banderas is a bit-player for most of it, despite his character being an openly gay ethnic minority, and his possibly intriguing arc is completely sacrificed, which is a bit of a shame because it’s a largely unexplored avenue.

Overall, Philadelphia is a lot like a piece of Ikea furniture – it’s got excellent parts, does what you want and when you’re finished you’re proud, but feel drained rather than overwhelmed.

7/10: As long as you don’t ask it to be anything more than it is, Philadelphia is an enjoyable, occasionally truly poignant movie with some virtuoso sequences and an astonishing central turn from a generation’s finest actor. It’s not going to change your life, nor make you want to protest for the rest of it, but it might just make you think a little harder about how you see the world. And that is what Andy Beckett, Jonathan Demme, and maybe even Ron Vawter, would call very commendable.

Luke Grundy is a fervent assimilator of media living amid the bright lights of London, England. If he’s not watching films or listening to music, he’s probably asleep, eating or dead. An aspiring writer, journalist and musician, he is the creator of movie/music blog Odessa & Tucson and lives for epistemology.

Luke Grundy is a fervent assimilator of media living amid the bright lights of London, England. If he’s not watching films or listening to music, he’s probably asleep, eating or dead. An aspiring writer, journalist and musician, he is the creator of movie/music blog Odessa & Tucson and lives for epistemology.

Leave a Reply