The Extreme World of Eraserhead

The world of David Lynch’s great 1977 film Eraserhead is, before anything else, a world of extremes: extremes of image, situation and sound which together evoke extremes of feeling, whether of alienation, revulsion or even of laughter.

Yes, laughter. For if a deep sense of unease seems to be the most common reaction, some viewers also claim to see humor in Henry Spencer’s perpetually worried visage in the face of nightmarish industrial landscapes, miniature theaters of horror, bizarre in-laws and a monster baby. To be sure, this is not a laughter of guffaws, but a deep-seated amusement.

In the end such a response may say more about the viewer than the film, and yet one cannot deny that Eraserhead is too intentionally artificial to be a complete gross-out. Even the most extreme moment of the film, when Spencer literally loses his head, a crescendo of panic and sound, takes place on a stage, emphasizing the point: these are scenes constructed just for you, the viewer. But what is the purpose of this? Why force such an extreme of artificiality?

Salvador Dali, The Angelus of Gala

The parallel to Surrealism is obvious. Dream and reality merge into an object of macabre beauty that goes, via Dali, to the heart of French Surrealism. Near the beginning of the film we see a beautiful portrait of Spencer that is reminiscent of one of Dali’s images of a woman seen from behind. Dali, like Lynch, had a classical control over his materials. The many years it took to make Eraserhead are not simply due to economic deprivation, but also to a master craftsman in the making, struggling to get it just right.

The film is equally reminiscent of Kafka in its radical bifurcation of what one might provisionally term normal life next to a naked vision of the subconscious, resulting in a profound feeling of alienation.

In melding realism and artifice Lynch merged two discourses or modes of perception that are generally seen as distinct. This is exactly what Dali did in painting and Kafka did in fiction.

It would be a mistake to assign specific symbolic referents to the images of Eraserhead. We see a schizoid world of extremes. The cheeks of the performing girl are a grotesque distortion of cuteness. Even the baby, monster that it is, manages to be cute. These images represent the melding of two contrary states, the cute and the monstrous, within a dyad of artifice and realism. A dyadic structure is repeated in subsequent films, whether in the pairing of light and dark, in and out, social veneer and underbelly, innocence and guilt or dream and reality.

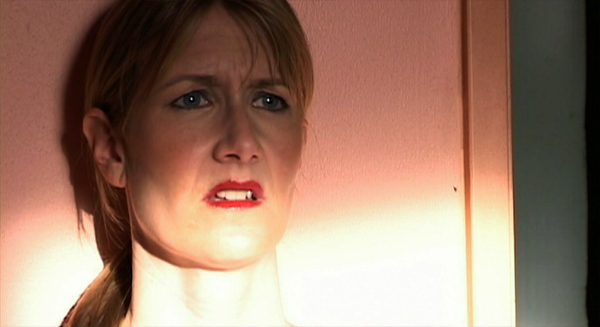

Still from Inland Empire

Still from Inland Empire

We have seen that Lynch merged two modes of perception in the images of Eraserhead. He did the same with narrative, resulting in a juncture of two discourses which we might give various designations to: poetic and literal, dream and reality or mundane and absurd, all within the scope of the artifice/realism dyad. The metaphor of an “eraserhead” is fractured into several senses. One is the alienation between people, the perpetually worried look on Spencer’s face being the reflection of a fundamental inability to perceive the “contents” of anyone else’s head. Profound confusion within one’s own being, profound uncertainty, is another sense; one does not know one’s self. And we have the very striking formal narrative transition that takes place when Spencer’s head literally becomes an eraser. If any “meaning” speaks through this film, it is the sense that our world of work and industry, taken to its extreme, strips us of all connection to the earth. The arrangements of grass and dirt in Henry’s apartment are very poignant seen in this context. Our human-made world strips us of a connection to the cosmos, to what Bataille termed the sacred, and in the extreme it destroys us by transforming us into just another object. Lynch makes this explicit even in cliché, as in the pre-dinner outburst of Henry’s future father-in-law: “I’ve seen this neighborhood change from pastures to the hellhole it is now!”

Nothing could be more natural or more vital for survival than procreation. Yet Henry can only produce a monster whom he does not recognize. He tries to. The only smile in the film comes when the baby gives him a passing sensation of pleasure. But when Henry finally sees himself as the monster he has engendered, he kills the baby. (That is also a laugh—of relief. Yes, I triumph!) Just as Lynch makes the monster baby cute at times, forcing the identification, he also makes an actual bitch suckling her young grotesque (largely through the use of sound), getting the viewer right into the face of the problem.

Another tragicomic image from the film is that of Spencer walking around in his printer’s uniform, even though he’s on vacation. When he looks in his mailbox he finds a tiny spermatozoa-like specimen, a seed of the monster he creates and that, ultimately, he sees himself as. This has come to him from the outside, and yet it is what he himself has created. Why force the issue of artificiality in Eraserhead? Perhaps it is to enable us to see the ways in which our human-made world is out of sync with the natural world, and in doing so we may recognize ways in which the very world we make destroys us. If we can’t do this then we may as well have erasers for heads.

Mark Kerstetter writes poetry, fiction and essays on art and literature. He loves to draw and make art out of wood salvaged from demolition sites. His poem Down the Rabbit Hole: Watching Lynch’s Inland Empire, or Goodbye Kurt Vonnegut, published in Unlikely 2.0, was largely inspired by David Lynch. He writes The Bricoleur.

Mark Kerstetter writes poetry, fiction and essays on art and literature. He loves to draw and make art out of wood salvaged from demolition sites. His poem Down the Rabbit Hole: Watching Lynch’s Inland Empire, or Goodbye Kurt Vonnegut, published in Unlikely 2.0, was largely inspired by David Lynch. He writes The Bricoleur.

[…] [7] http://www.escapeintolife.com/movie-reviews/the-extreme-world-of-eraserhead/ […]

Excellent essay. One of the most insightful I’ve read so far on this film.

[…] Read my essay on Lynch’s Eraserhead […]