Via Basel: The Gift

A conversation about The Gift, by Lewis Hyde, between Basel Al-Aswad, EIL Columnist, and Kathleen Kirk, EIL Poetry Editor.

A conversation about The Gift, by Lewis Hyde, between Basel Al-Aswad, EIL Columnist, and Kathleen Kirk, EIL Poetry Editor.

On Saturday, January 24, 2015, I met with Basel Al-Aswad at the former home of his son, Christopher R. Al-Aswad, our founding editor. Chris lived across the street from a field—sometimes planted with corn, sometimes beans. On that winter day, it was a bare, harvested field recently covered with snow. Oddly, in mid-January, we’d enjoyed “the gift” of 40-degree weather and sunshine, the snow had completely melted, and I found Basel sunbathing in the kitchen in a lawn chair at the back patio doors, a breeze coming through the screen. We sat in the sun for a while before moving to the dining room table to converse, take notes, and compare our editions of The Gift, by Lewis Hyde. –Kathleen Kirk

Kathleen Kirk: Basel, let’s talk a bit about the coincidences in connection with our reading this book together. I’m re-reading it, and you’ve been reading it for the first time. I remember when you told me over the phone that you were reading a book called The Gift. “By Lewis Hyde?” I asked. “I know it well! I read it thirty years ago!”

Basel Al-Aswad: This fall, my friend Lisa Wainwright at the School of the Art Institute in Chicago invited me to a lecture, dinner, and discussion with the author. I went, not knowing anything about the author or his topic. I listened to his presentation and got to meet him briefly, and, because the subject matter was very interesting to me, I read the book. It’s very interesting to read a book after meeting the author. I was intrigued by his concept of gifting vs. commodity, and I wanted to learn more. I’m a doctor, a surgeon, and, until now, more connected to scientific medical literature. You could consider me a layman when it comes to literature and poetry.

Kathleen Kirk: But now you know a lot about Walt Whitman and Ezra Pound because of the chapters devoted to those two poets in this book. I knew of The Gift from way back when I was a student at Kenyon College. A chapter from The Gift was first published in the New Series of the Kenyon Review. As I recall, Hyde was coming to teach in the Integrated Program in Humane Studies. Now he is the Richard L. Thomas Professor of Creative Writing, teaching at Kenyon in the fall semesters.

Basel Al-Aswad: He has also taught at Harvard.

Kathleen Kirk: Let’s compare our editions. I have the 1983 paperback edition with a Shaker illustration of a basket of golden apples on the cover.

Kathleen Kirk: Let’s compare our editions. I have the 1983 paperback edition with a Shaker illustration of a basket of golden apples on the cover.

Basel Al-Aswad: I’m reading it on my Kindle, but mine is the 25th-anniversary edition, from 2007, with a different subtitle: Creativity and the Artist in the Modern World.

Kathleen Kirk: You have the pink heart cover. Mine has the subtitle Imagination and the Erotic Life of Property, and that’s from a definition of eros as the kind of love or desire that is a creative life force. Let’s see if we have the same Introduction. Mine begins with an epigraph by Joseph Conrad: “The artist appeals to that part of our being…which is a gift and not an acquisition—and, therefore, more permanently enduring.”

Basel Al-Aswad: Yes, mine, too.

Kathleen Kirk: And the text of this Introduction begins, “At the corner drugstore my neighbors and I can now buy a line of romantic novels written according to a formula developed through market research.”

Basel Al-Aswad: Yes, but mine also has a Preface and an After Word. My edition has the advantage of perspective. It’s seen through the lens of time. He was so right about everything, and we can see that now, as what he said about the materialism of the 20th century was so true, and it intensified as we entered the 21st century.

Kathleen Kirk: So the examples in the book are not updated, but the Preface and After Word update us and help us see how correct he was. His thesis still holds: “It is the assumption of this book that a work of art is a gift, not a commodity. Or, to state the modern case with more precision, that works of art exist simultaneously in two ‘economies,’ a market economy and a gift economy. Only one of these is essential, however: a work of art can survive without the market, but where there is no gift there is no art.”

Basel Al-Aswad: Lewis Hyde said that he speaks to all kinds of artisans, not just artists and writers and poets, though poetry is what got him interested in all this. He explains early in the book that he was a poet first. I suggest that he also speak to scientists and doctors. He crosses barriers and disciplines with his ideas. He covers the three main aspects of our life in what he says about “the gift” and its circulation—spirituality, science, and art.

Kathleen Kirk: An aspect of the richness of this book—it gives us mythology and folk tale, sociology and economics and anthropology, as well as a close look at two poets. Basel, a side note. Do you know that one of our Escape Into Life poets is an economist who has just co-authored a book on “the humane economy”? I think I recommended The Gift to her, but she and her co-author were reading a lot of contemporary works of traditional economics. Of course, like you, I think everybody should read The Gift. It covers so much.

Kathleen Kirk: An aspect of the richness of this book—it gives us mythology and folk tale, sociology and economics and anthropology, as well as a close look at two poets. Basel, a side note. Do you know that one of our Escape Into Life poets is an economist who has just co-authored a book on “the humane economy”? I think I recommended The Gift to her, but she and her co-author were reading a lot of contemporary works of traditional economics. Of course, like you, I think everybody should read The Gift. It covers so much.

Basel Al-Aswad: It explains everything so well. Usury, the section on usury! It explains how and when various religions used or justified usury. Within the circle of the family or the community, no usury is allowed. Only the gift. Outside the circle, it’s OK. You give a break to family members. Outside the circle, it’s what the market will bear.

Kathleen Kirk: Interestingly, A Tempered and Humane Economy, by Jannett Highfill (our EIL poet) and Patricia Podd Webber, explains how giving family members a break can sometimes destroy a small family business trying to survive in a market economy! Hyde would agree that it can be dangerous to try to mix the gift economy and the market economy.

Basel Al-Aswad: Another coincidence is this, yesterday’s New York Times. It has this picture of Walt Whitman’s poem to Abraham Lincoln—“O Captain! my Captain!”—in his own handwriting. Hyde gives us that whole chapter on Whitman. Now when I go back to read Whitman’s poems, I will understand them so much better because I know his background from The Gift. Whitman was a man without barriers. My son Chris was like this, too. He had no barriers, he would say anything, and he was good at listening. He was good in the intimate setting, and he had international friends that became his intimate friends through the Internet. He wanted to be an artist, but he knew he had to make a living. He knew that what he had with Escape Into Life was pure gift, not commerce, but he founded it as a dot com, looking for some kind of sustainability. He had that conflict as an artist. Gift vs. commodity. Chris got EIL going with his mother’s trust fund, and now the family keeps it going, so Escape Into Life is his continuing gift.

Kathleen Kirk: I see that parallel with Whitman. Chris told his personal story in memoir, fiction, and even a graphic novel account of himself, all shared on the Internet, and it drew people to him. In The Gift, Lewis Hyde looks at the epiphanies in Whitman’s famous poem, “Song of Myself,” as being about breaking down all barriers between beings. Chris was singing a kind of “Song of Myself” with the new technology. Hyde describes a hunger fantasy of Whitman’s and its transformation into poetry via the circulation of gifts: “The sequence of events implies that Whitman shared the bread with his soul, and now the soul has given him a return gift, his tongue.” That’s the poet’s gift, the ability to sing! “In the circulation of gifts Whitman becomes a poet, or, to put it another way, through the completed give-and-take he enters a way of being, a state, in which an ongoing commerce of gifts is constantly available to him.”

Kathleen Kirk: I see that parallel with Whitman. Chris told his personal story in memoir, fiction, and even a graphic novel account of himself, all shared on the Internet, and it drew people to him. In The Gift, Lewis Hyde looks at the epiphanies in Whitman’s famous poem, “Song of Myself,” as being about breaking down all barriers between beings. Chris was singing a kind of “Song of Myself” with the new technology. Hyde describes a hunger fantasy of Whitman’s and its transformation into poetry via the circulation of gifts: “The sequence of events implies that Whitman shared the bread with his soul, and now the soul has given him a return gift, his tongue.” That’s the poet’s gift, the ability to sing! “In the circulation of gifts Whitman becomes a poet, or, to put it another way, through the completed give-and-take he enters a way of being, a state, in which an ongoing commerce of gifts is constantly available to him.”

Basel Al-Aswad: And that could also describe Escape Into Life, an “ongoing commerce of gifts.” One of Chris’s dreams before he died was for EIL to have an Art Store, so we put that in place for him. We tried “selling” art there, but that didn’t work. So now the EIL Store functions as a place for people to connect with the artists themselves, if they want to purchase art. EIL provides a free platform and does not complete the purchase or take a commission. The EIL Store lets people find and connect with the artists they like.

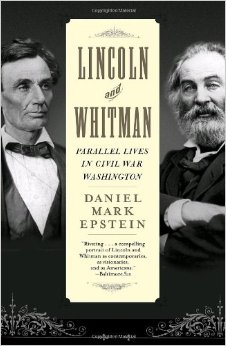

Kathleen Kirk: Here’s another coincidence for you. A few years ago, I read this wonderful book by the poet Daniel Mark Epstein, also from Kenyon, called Lincoln and Whitman: Parallel Lives in Civil War Washington. It’s about how they knew of and admired each other but—

Kathleen Kirk: Here’s another coincidence for you. A few years ago, I read this wonderful book by the poet Daniel Mark Epstein, also from Kenyon, called Lincoln and Whitman: Parallel Lives in Civil War Washington. It’s about how they knew of and admired each other but—

Basel Al-Aswad: They never met!

Kathleen Kirk: They’d see each other from across the street in Washington and nod to each other, or tip their hats, but, as Hyde tells us, Whitman took off his hat to no man!

Basel Al-Aswad: It was part of his feeling of equality because there are no barriers. And Whitman was so humble in service, and generous, nursing the Civil War soldiers. That generosity of spirit is crucial to the idea of the gift. Hyde is generous even toward Ezra Pound. I had no idea who Ezra Pound was, the details of his treasonous activities in World War II, how he was a kind of villain. But Hyde explains it so well that you see there is a certain…wisdom in it, what Pound thought, his idea of art vs. capitalism. Pound interpreted Fascism as offering a kind of extreme equality that he thought would be good for the artist in the society.

Kathleen Kirk: You understood Pound’s Fascism better through what Hyde had to say about it.

Basel Al-Aswad: Yes, he softens the ideas of Ezra Pound by approaching them with logic and compassion.

We’ll give you the rest of our conversation in a future Via Basel column, and we hope you’ll seek out The Gift, by Lewis Hyde, at your library or bookstore, and learn more about him at the links below. Here’s yet another coincidence connected to a guest speaker at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC). Many years ago, my husband and I went to hear the famous French sociologist and philosopher, Jean Baudrillard, speak to students at the SAIC. His ideas were similar to Hyde’s, in that he pointed out that the art world had been overtaken by art as commodity and art as investment, managed by galleries, instead of art as creative expression, generated by artists. In the discussion period afterward, students kept talking about the art they were making, using intellectual terms to describe it. Finally, in good-natured exasperation, Baudrillard said, “Stop saying you are making art! You are making commodities!” A few of them got it, for someone finally asked, “What should we do if we want to make art?” It was a gentle answer, a traditional answer, a simple and lusty answer: “Get a loaf of bread, a jug of wine, and take someone you love down to the edge of the river. Then you’ll be able to make some art.” –KK

Basel Al-Aswad, father of EIL founder Chris Al-Aswad, is a yogi trapped in an Orthopedic Surgeon’s body. His loves in life include reading, hiking, enjoying nature, meditation, and spending time with his large Iraqi family.

Basel Al-Aswad, father of EIL founder Chris Al-Aswad, is a yogi trapped in an Orthopedic Surgeon’s body. His loves in life include reading, hiking, enjoying nature, meditation, and spending time with his large Iraqi family.

Lewis Hyde at the School of the Art Institute

Lewis Hyde at the Radcliff Institute for Advanced Study, Harvard University

Lewis Hyde the Berkman Center for Internet and Society

Really enjoyed this! Thank you.

Nice discussion, I enjoy the comparisons. Emil is presently reading The Gift! Thanks to you. I will read it when he is done with it. Thank you, Basel!

i enjoy it very much and i am going to read the book. thank you and keep on doing !!!