Pablo Gonzalez-Trejo

“Joe“, #86 by Pablo Gonzalez-Trejo

In 1988 a pipe bomb exploded at the Cuban Museum of Arts and Culture in Miami. The problem? There were people on the museum’s board who wanted to offer to the public the work of artists currently living in Cuba or who had not openly criticized Castro. By 1999 the museum, which had opened in 1973 (the year a boy named Pablo Gonzalez-Trejo was born in Sancti Spiritus, Cuba), closed its doors, having been dogged by the fight between artistic freedom and the brutal tactics of the Castro haters.

July, 2009. Freedom Tower, Biscayne Boulevard: the public was cordially invited to come inside and view the large charcoal portraits by Pablo Gonzalez-Trejo—and deface them. The portraits were of notorious dictators: Hitler, Stalin and yes, Castro. This is Miami, just what one might expect. And yet there was one other portrait open for defacing—that of our former president, George W. Bush.

Laurent, by Pablo Gonzalez-Trejo

To say that our culture is fascinated by destruction will hardly shock anyone. In 1911, during modernism’s robust adolescence, hordes went to see the blank spot formerly occupied by the stolen Mona Lisa. And in modernism’s grand age, just after September 2001, people went to Ground Zero to gaze upon a blank space. Herbert Muschamp, architecture critic of the New York Times, asked, “Does destruction capture the imagination more than buildings?”

It is a question that Trejo’s art asks. When he says, “We are no more than just a metaphor of ourselves,” he means that a person’s identity is always changing, never solid. We make as well as destroy each other.

Skull #75, by Pablo Gonzalez-Trejo

Maybe that’s why his durable works—the oil paintings—depict either corpses, slabs of meat, masked figures or images of the body disengaged from a recognizable face. Thief depicts an armed robber in a ski mask. It’s as if the man is getting away with something by being held captive for posterity in the fine old cast of oil paint and canvas. Others are victims of suicide or gun shots—only the dead and those who carefully conceal their identity are fit subjects for Trejo’s paintings.

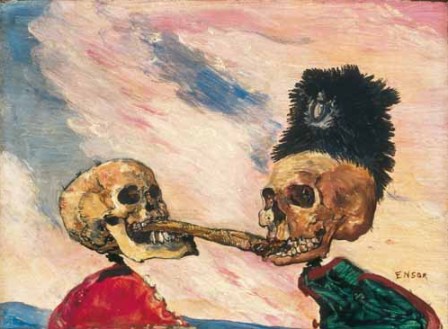

Just as it is no stretch to see a picture of Castro open to immolation in Miami, it is not difficult to appreciate the painterly tradition that is embraced by these paintings. Trejo uses a stroke reminiscent of Soutine, dabs of impasto reminiscent of Van Gogh, colors that Gauguin might have admired, and a secure building of form worthy of Ensor. He’s a hell of a painter.

![]() Mark Kerstetter steals time away from restoring an old house in Florida to write and make art. His poetry is forthcoming in the July 4th issue of Unlikely Stories and he is the author of the blog, The Bricoleur.

Mark Kerstetter steals time away from restoring an old house in Florida to write and make art. His poetry is forthcoming in the July 4th issue of Unlikely Stories and he is the author of the blog, The Bricoleur.

Hi,… just saw this show in Ghent Belgium that represents comtemporary links to James Ensor

http://www.visitgent.be/smartsite.dws?ch=VGG&id=10757&vg_lang=EN

Hareng saur – Ensor and contemporary art

It is a well-known fact that James Ensor (1860-1949) was one of the pioneers who paved the way for modern art. During his lifetime his home in Ostend was a haven for artists and intellectuals. Two museums, the Museum of Fine Arts and the Municipal Museum of Contemporary Art, have joined forces to examine the relationship between James Ensor’s visionary art and the artistic practice of a host of contemporary artists in the exhibition, “Hareng saur – Ensor and contemporary art”.

The exhibition will be inaugurated on 30 October with a free opening party for everyone starting at 2 pm. The event will include a performance by Belgian artist Jozef Legrand.

More here on Ensor show http://www.smak.be/tentoonstelling.php?la=en&y=&tid=&t=&id=482