The Babylon Line

The Babylon Line by Richard Greenberg

Directed by Terry Kinney

Lincoln Center Theater at the Mitzi E. Newhouse

Reviewed by Scott Klavan

December 7, 2016

Levittown, Long Island, 1967, and the people stay close to their middle-class planned neighborhood, even hide inside their homes, and when they pack up and move, they move across the street. This is the way it is for the characters in Richard Greenberg’s new play The Babylon Line, directed by Terry Kinney and presented by Lincoln Center. War veterans and housewives, complacent, narrow and provincial, secretly sorrowful, live here. But searching for something else, a new kind of illuminating experience, or merely by mistake, four local middle-aged women and two men take an adult ed writing class taught by Aaron Port, 38, a unfulfilled fellow with one published short story to his name. Port makes the “reverse commute” from Manhattan’s Greenwich Village to The Island, needing a few extra bucks, and, maybe looking to get out of and into something himself.

Under Aaron’s diffident yet oddly inspiring leadership, the students struggle to come up with essays and stories; all finally in their own way make breakthroughs, lurch ahead. Or, do they? Just as the country is fitfully riding a wave of upheaval, upending traditions, beliefs and behavior in the late ‘60s, the students battle with forces inside and outside of themselves, torn between following rules and breaking them, between love and loneliness, commitment and abandon. Ultimately, the characters on stage are forced by their own unconscious to confront the questions: is this Success? Failure? Courage, cowardice? Transcendence or stasis?

The play itself faces these same vacillations and tests. The Babylon Line features long sections of brilliance, knife-sharp simultaneous combinations of wry humor and lacerating heartbreak. For two hours and ten minutes, this is one of, if not the, smartest, most involving, daring plays of the last ten years. But in the final five minutes, the playwright and production hold off and chicken out, pissing it all away.

The primary students in Port’s class are Jewish women of the old school: Frieda Cohen (Randy Graff), brassy, unrepentantly judgmental, devoted to her two sons, suspicious of anything that threatens the crumbling brick structure of traditional family life; Midge Braverman (Julie Halston), hiding a stingingly unhappy marriage beneath quasi-intellectual pronouncements and stories of European vacations; Anna Cantor (Maddie Corman), gawky and outgoing, with a simplistic yet sincere openness to change. The male students sit on the periphery: Jack Hassenpflug (Frank Wood), a barely communicative World War II vet who dreams of battle scenes, whose waking days are a fog of marital banality; Marc Adams (Michael Oberholtzer), the youngest student, a once-bright fellow who, due to drug use or mental turmoil or both, has lapsed into grinning monosyllabism. There’s one other student: Joan Dellamond (Elizabeth Reaser), a sexy southern transplant and gentile, a mysterious restless woman emerging from years of agoraphobia caused by her infertility with a similarly damaged husband. Joan is immediately and intensely drawn to married teacher Port (Josh Radnor). While Port enables Joan to write compelling, unsettling stories, including a possibly false tale of her kicking a baby in her yard, he cannot bring himself to act on/succumb to her increasingly desperate seductions.

The adult ed set-up is not new. Recently, we have seen it onstage in Annie Baker’s Circle Mirror Transformation and Hand To God, by Robert Askins. But The Babylon Line is better written, denser and more adult. The first act is a consistently absorbing and surprising series of revelatory scenes and speeches. Playwright Greenberg presents his characters as a composite of ridiculous, shameful, even angering flaws, and nakedly poignant needs and vulnerabilities. Mrs. Cohen’s defense of her family life is pinched yet has a kind of heroically devoted single-mindedness; Mrs. Cantor’s story of learning to mow her own lawn to satisfy Alfred Levitt, the god-like designer of this model post-War suburban neighborhood, is an example of the writer’s ability to make small incidences attain a gigantism. Joan is off-putting in her self-involvement, yet we cannot but help but be drawn into her bereft sensuality, her blatant lonely horniness. (Yes, there are some factual issues here. Some of the references to Levittown are historically wrong. The Holocaust, a calamity that seeped into the very wallpaper and furniture coverings of this time and place, is never mentioned. But the play doesn’t need to be a documentary on Jewish suburban social history.)

The second act bucks the trend, often lamented in my columns here, for non-musical plays to be modest works of 90 minutes, with two characters, etc. In fact, it valiantly flies in the face of it: here we have seven actors and a swirling, ballooning group of scenes that head into the past and future, depicting crimes, suicides, fantasies, and hard-nosed reality. And, almost all the way through—until the ruinous finish, which we’ll get to shortly—it works, because the unhinging of the dramatic structure reflects the expanding, exploding inner lives of the students, and because Greenberg’s writing is so fine. The details of the characters’ lives and relationships, their confusion, anguish and sincerity, are exceptionally expressed, carrying us through.

And the acting, as always in top-level NYC shows, but even more so here, is great. Randy Graff creates a classic characterization in Mrs. Cohen; proud, haughty, colorful, defensive and aggressive. Julie Halston, as a decent woman hiding her shame and disappointment, lets a pained softness creep into Mrs. Braverman’s breezy readings of her family trips. Maddie Corman’s offbeat physicality is fantastic; the flying arms-and-legs, open-mouthed toothy smiles providing hints of the unconventionality that will lead Mrs. Cantor to bolder late-life choices. The performances of the men are cheated here, as the male students are not given enough to do. But within that stricture, acclaimed Broadway veteran Frank Wood as Hassenpflug mixes a Honeymooners Norton goofiness with a bewildered rage. Michael Oberholzer, so effective in Hand To God, does well with a one-note part as Adams, and shows terrific range in his bits as other characters.

Elizabeth Reasor in the pivotal role of Joan, is really brave here, and portrays excellently the woman’s uneducated intelligence and almost infinite sexual resourcefulness. As Port, the ostensible lead and occasional narrator, Josh Radnor is highly appealing and capable; as he did in Disgraced last year, he does a super job handling the delicate humor of the language. What’s missing in the performance is what Joan calls the “pleasant promise of violence” in the teacher, a man she later describes as a “firebrand.” It may be intended that Joan, frustrated by the impotence in the men in her life, needs to see him this way, but, even so, the character would seem to require that electricity, as well as a burning need for Joan, even if it’s only something that roils up inside of him and is never fully acted upon. If Port is already beaten, in control, as he is here, there’s nothing to reign in. But to be fair, the restraint may be a writer/director/producer idea Radnor was following.

Director Terry Kinney, one of the founding members of Chicago’s famed Steppenwolf Theatre Company, and a longtime actor in shows including The Grapes Of Wrath—as well as the director of Roundabout’s upcoming revival of The Price—keeps this longish, difficult work buoyantly interactive. Dialogue that could be literary is here human and dynamic, a credit to his leadership. At times, he seems hampered by the set by Richard Hoover, which while wonderfully real and evocative of the time period, is static and unmovable. This causes the growing array of memory scenes in the second act to be staged rather inelegantly under lights anywhere they can figure to put them. But it doesn’t hurt very much.

Richard Greenberg is one of America’s most prolific and admired major playwrights, winning a Tony for Take Me Out and earning success with other works including Three Days Of Rain. The Babylon Line began upstate at New York Stage & Film and Vassar’s Powerhouse Theater in 2014. In many ways, this is his best play. But, as mentioned, the very ending of the piece goes aground. (The finale of Stephen Karam’s The Humans, reviewed here, was also misguided, but, apparently, seemed ambiguous enough to pass muster with the audience.) It is not exaggerating to say that Babylon’s conclusion, theater-wise, is a tragic mistake.

[Spoiler alert! Tragic mistake to be revealed…!]

Joan cajoles, orders, and otherwise tries to a wangle a kiss out of Port. But all to no avail; he even retells the scene of their final class meeting, supposedly to “redo” it, and then, still does nothing. Given what has come before, and the themes inherent in the play, this is an impossible choice. To say it clearly: the play cannot end this way. There is something about the teacher that gets the students to open up and explore themselves. It’s not enough, and just untrue, to say that the students do it alone, and use Port simply as a tool to redemption. He may not act on it, the kissing scene may be a dream or a wish, but it has to be there, onstage, because it’s his soul that is the catalyst, that influences the staid suburbanites in front of him, and us. Port, after all, denies being a “nice Jewish boy,” has moved out of Long Island to the Village and has married a non-Jewish woman; he has the capacity. He talks about loving his wife, which is sweet, but in the context of the play, who cares? His soul has to be transgressive, because it represents the possibilities in all of us, to rebel against our own inhibitions and fears, and the restrictions of life. If we don’t have the seed, the potential, how can we hope, try and succeed, or flee and fail?

On a technical dramatic level, it also kills things. While a novel by Henry James can tell a story about a non-action/event, with stage plays, not-so-much. Hamlet: “To be or not to be—ah, no point, forget it.” The curtain comes down. After the end of The Babylon Line, this reviewer turned to the stranger sitting in the next seat and said: “He has to kiss her. Otherwise, there’s no play.” She nodded and replied immediately, without blinking: “Of course.” When the audience knows better than the playwright, there’s a problem. President Hillary Clinton can attest to the risks of making a prediction about group activities, but the tepid response by the audience to the curtain call seems to have come from their dissatisfaction caused by Port’s final inaction, and an educated guess would be that it will keep The Babylon Line from moving to a bigger, Broadway house (technically, Lincoln Center’s smaller Mitzi E. Newhouse is Off-Broadway) and/or getting the honors and attention it otherwise deserves.

Why this decision was made is unknown but it does have the sour whiff of the contemporary sexual politics that claims a woman being freed/redeemed/rescued by a kiss from a man is a corny, false desire and somehow demeaning. But politics is full of dissembling; it traffics in the temporary Lie Of The Day. Art has to be better than that; it has to have the guts to seek and portray the everlasting truth. Maybe the production was scared that a man’s kiss of a woman would be too standard and traditional a closing vision. But Greenberg has deftly written a play where after all the dizzying hardship the characters have received from life or unwittingly brought on themselves, the most expected action is the one that’s ironically, the most audacious, and necessary. So:

Kiss The Girl.

Scott Klavan, theatre writer at Escape Into Life, is an actor, director, and playwright in New York. Scott performed on Broadway in Irena’s Vow, with Tovah Feldshuh, in regional theater, and in numerous shows Off Broadway, including The Joy Luck Club. His stage adaption of Raymond Carver’s short story “Cathedral” was produced off-Broadway by Theater by the Blind (TBTB, now Theater Breaking Through Barriers), and his play Double Murder was published inBest American Short Plays of 2006-2007. For twenty years, Scott was Script and Story Analyst for the legendary actors Paul Newman and Joanne Woodward. In 2014, he starred in A Soldier’s Notes, an episode of the new Web Series Small Miracles, alongside Judd Hirsch, earning him a nomination for Outstanding Actor in the LA Web Series Festival 2015. He directed the one-woman show My Stubborn Tongue, written and performed by Anna Fishbeyn, at the United Solo Festival in New York, and a series of staged readings of a new comedy, Sheila & Angelo, at the Dramatist Guild. In 2015, he appeared in the Off-Broadway production of the musical Sayonara, for Pan Asian Rep. Scott directed and appeared in the solo play Canada Geese, by George Klas, in the 2016 NY International Fringe Festival.

Scott Klavan, theatre writer at Escape Into Life, is an actor, director, and playwright in New York. Scott performed on Broadway in Irena’s Vow, with Tovah Feldshuh, in regional theater, and in numerous shows Off Broadway, including The Joy Luck Club. His stage adaption of Raymond Carver’s short story “Cathedral” was produced off-Broadway by Theater by the Blind (TBTB, now Theater Breaking Through Barriers), and his play Double Murder was published inBest American Short Plays of 2006-2007. For twenty years, Scott was Script and Story Analyst for the legendary actors Paul Newman and Joanne Woodward. In 2014, he starred in A Soldier’s Notes, an episode of the new Web Series Small Miracles, alongside Judd Hirsch, earning him a nomination for Outstanding Actor in the LA Web Series Festival 2015. He directed the one-woman show My Stubborn Tongue, written and performed by Anna Fishbeyn, at the United Solo Festival in New York, and a series of staged readings of a new comedy, Sheila & Angelo, at the Dramatist Guild. In 2015, he appeared in the Off-Broadway production of the musical Sayonara, for Pan Asian Rep. Scott directed and appeared in the solo play Canada Geese, by George Klas, in the 2016 NY International Fringe Festival.

The Babylon Line at Lincoln Center Theater

Scott Klavan’s review of Heisenberg at EIL

Scott Klavan’s review of The Humans at EIL

Scott Klavan’s review of Hand to God at EIL

Scott Klavan’s review of Disgraced at EIL

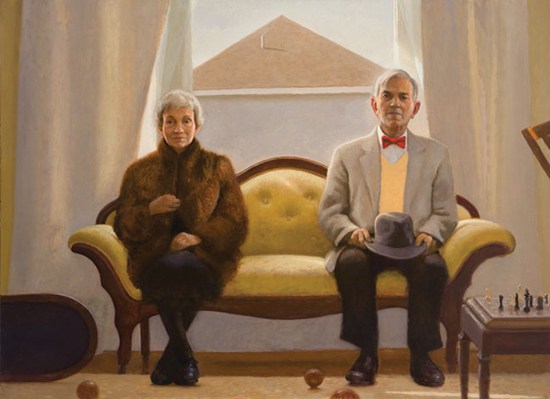

More art by Bo Bartlett at EIL

Bo Bartlett—Paintings of Home, a review by Meredith Rosenberg at EIL

Leave a Reply