Listening to Judy Chicago

The Dream, 1940. page 149 of Frida Kahlo: Face to Face

Skeletons play a prominent role in Mexican folk art, particularly in the annual Day of the Dead festivities. This holiday has its origins in a pre-Hispanic worldview, based on the idea that birth leads to life and life leads to death in an endless cycle, a perspective that underpins many of Kahlo’s paintings. – Judy Chicago

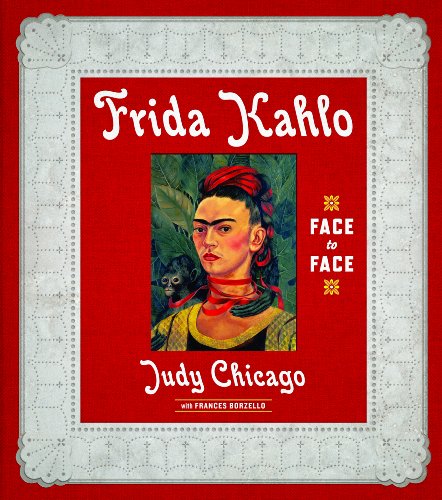

Judy Chicago, minimalist painter and pioneer of feminist art, Through the Flower, has published a new book, Frida Kahlo: Face to Face (Prestel, October 2010), celebrating the event with a lecture tour around the United States.

On her second stop, at the National Museum of Women in the Arts, in Washington, D.C., where Kahlo’s Self-Portrait Dedicated to Leon Trotsky (1937) is on view in the museum’s permanent collection galleries, I had the privilege of joining a full house to hear Judy Chicago talk of how she came to write the book, the discoveries made while doing so, and more personally, the inspiration Kahlo has been throughout the author’s own long career.

The book – 252 pages and weighing more than five pounds – was not her idea she noted at the outset of the talk. Prestel Publishers’ editor-in-chief, Christopher Lyon, wanted to do a book on Kahlo and turned to Judy Chicago whom he recalled was responsible for his own introduction to the artist via a more than three-decades-old lecture of hers he’d come upon by chance. In the 1970s, while researching her largely ignored artistic predecessors and colleagues who were women, the author had learned that not only was Kahlo not so well known; she was, if thought about at all, typically and dismissively viewed as “the wife of Diego Rivera, who also paints”. Chicago agreed to do the book on condition she could work with the art historian Frances Borzello and Lyon accommodated.

Self-Portrait on the Borderline between Mexico and the United States, 1932 , on page 112 in Face to Face

Machines were a symbol of alienation in her work, and the ones she includes, relatives of those Rivera was currently glorifying in his murals, seems like an army on the move. Typical of the symbolic shorthand she was rapidly developing to visually express her feelings is the contrast between the plug in the plinth attached to a motor on the U.S. side and the rooted plants on the Mexican side. – Frances Borzello

The approach of artist and historian to Kahlo as subject, the author explained, was to look at Kahlo’s career and oeuvre as a whole; in particular, to situate Kahlo’s self-portraiture in the history of female self-portraiture. In this way, Chicago and Borzello were able to engage on the page in a “face to face” dialogue about Kahlo’s paintings, to go beyond biography to reveal how Kahlo – who was an intellectual, bisexual, surrealist Communist – prefigured many foci of feminist art and, through her painting, also broke the silence about the legitimacy of women’s experiences as subjects for art.

Chicago’s and Borzello’s commentaries about Kahlo’s significant work, images of which are reproduced in full color in Face to Face, range across nine themes, each of which she described briefly over the course of her talk: family and friends, mirror images, Mexican identity, Diego Rivera, Kahlo’s cosmology, Kahlo’s menagerie, fruits and flowers, the divided self, and the inside out.

We can learn from the writer’s informative and insightful perspective on the largely self-trained Kahlo whom, she said, the feminist art movement “brought into the mainstream”. To evaluate the artist through her biography – Kahlo’s path to art was through her father, Guillermo Kahlo, a photographer, and her husband Diego Rivera, one of the great muralists of the time – is to deny Kahlo her “artistic agency” Chicago stressed. To properly accord Kahlo her due, it’s necessary to challenge the “dominance of the male narrative” that reduces women’s artistic contributions to the sum of their biographical details as daughter, sister, wife, mother, or muse.

Just as Kahlo had been known primarily as Rivera’s wife “who also paints”, the author herself has been reduced to being described as “that woman who made The Dinner Party“, when her international career of more than 40 years encompasses roles as artist, author, feminist, educator, and intellectual. Other parallels Chicago said she shares with Kahlo include a father’s influence, a painful childhood, and use of color.

Sun and Life, 1947. page 154 Frida Kahlo: Face to Face

Historically, very few women artists have attempted to create a personal visual cosmology….Kahlo’s painting is bursting with fecund life-forms. In the center of the canvas is a plant that metamorphoses into a sun with a weeping third eye….Above the sun is a fetus while below it is a skein of roots and leaves. The composition seethes with life bursting forth yet the color of the plants is austere, as in the late fall when growth subsides and winter begins in preparation for the next spring when life will erupt again. – Judy Chicago

The achievements of artists such as Kahlo and Georgia O’Keeffe are reduced in importance when the artists are viewed as somehow an aberration or exceptional. The strategy for evaluating women’s artistic creations properly, Chicago made clear, must be to place them, one, in the context of the mainstream and, two, in the context of women’s own art history.

Kahlo demonstrated great skill in communicating subtly the pressures on women artists to portray themselves in certain ways: as infantilized and, even more clearly, as subservient to the men in their lives. For example, because of the cultural and social mores of her time, Kahlo could not, Chicago said, have painted herself as an artist; hence, in Kahlo’s 1931 double portrait, Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera, it is her hulking husband who holds the palette and brushes and she, outfitted in traditional dress, significantly smaller in stature (note especially the tininess of her feet), who demurely holds Rivera’s hand.

Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera, 1931. page 128 Face to Face

Rare for the time, Kahlo revealed through her paintings an intensely personal, vividly visual cosmology in which she betrayed her notions of the interconnectedness of everything. As evidence Chicago cited Kahlo’s masterpiece Moses, painted in 1945; it is, she pointed out, replete with historical and mythical figures, as well as symbols of life and death, yet it is not a painting that comes readily to the mind of the general public as, would, say, Kahlo’s self-portraits with her companion monkey. Nor has it been exhibited widely: the author suggested that one reason for the relative obscurity of the work is that although it was fine for a woman to paint self-portraits, it was not acceptable for a woman to paint images of the world.

Moses, 1945. page 157 Frida Kahlo: Face to Face

Much has been made of Kahlo’s self-portraits with companion animals, which, Chicago averred, ought not to be read as comments on her relationship with Rivera – thus diminishing that “artistic agency”. Instead they should be read as Kahlo’s emphasis on emotional and physical connections and her effort to render in painting emotions that she could not otherwise articulate directly, given the times in which she lived.

Self-Portrait with Monkeys, 1943. page 181 Face to Face

Kahlo’s decision to include so many animals in her self-portraits reveals how close she felt to the animal world….She expressed her alliance with the monkeys through their hands across her body, through ribbons uniting them both, or, in this case, through the monkey’s tail wound round her arm. – Frances Borzello

Kahlo’s oeuvre includes still lifes of fruits and flowers, a genre typically considered “suitable” for women who painted and so not to be taken seriously. Judy Chicago pointed out that close examination of Kahlo’s fruits and flowers, such as the lush Still Life (Round), (1942), reveals much more than a quick look or two might disclose; in it are symbols of distinct sensuality and sexuality and deep awareness of the cycle of life, death, and rebirth.

Still Life, 1942. page 190 Frida Kahlo: Face to Face

The author also spoke of how Kahlo, in paintings such as the graphic My Birth (1932), opened up the subject matter of women’s life experiences in a way that gave successive generations of women artists the psychological freedom to express themselves fully in and through their art. This pre-figuring of feminist art, of giving validity to suppressed emotion, is part of Kahlo’s great legacy, Chicago added.

Judy Chicago’s Through the Flower

Maureen E. Doallas has been a writer, editor, and features reporter for more than three decades, working in such diverse fields as international healthcare, education, and employment law. Now retired, Maureen owns her own small business, Transformational Threads, which licenses images of original fine art for reproduction in custom limited-edition hand-embroidery in Vietnam. Maureen also is a published poet, with poems forthcoming in the anthology Oil and Water. . . And Other Things That Don’t Mix, sales of which will benefit communities along the U.S. Gulf Coast affected by the BP oil spill, and at Red Lion Square. An avid collector of art and fine press books, Maureen blogs daily at Writing Without Paper, primarily about poetry and other literary, visual, and performing arts.

Maureen E. Doallas has been a writer, editor, and features reporter for more than three decades, working in such diverse fields as international healthcare, education, and employment law. Now retired, Maureen owns her own small business, Transformational Threads, which licenses images of original fine art for reproduction in custom limited-edition hand-embroidery in Vietnam. Maureen also is a published poet, with poems forthcoming in the anthology Oil and Water. . . And Other Things That Don’t Mix, sales of which will benefit communities along the U.S. Gulf Coast affected by the BP oil spill, and at Red Lion Square. An avid collector of art and fine press books, Maureen blogs daily at Writing Without Paper, primarily about poetry and other literary, visual, and performing arts.

[…] Listening to Judy Chicago « Escape Into Life […]